A new study has unearthed several telling facts about what white evangelical Protestants really think about America’s growing diversity.

The findings, published last Monday by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), suggest many white evangelicals don’t see eye to eye with Protestants of color on issues concerning race, immigration and President Donald Trump’s effect on white supremacists.

This racial gap could have lasting repercussions as American evangelicalism becomes more diverse.

PRRI found that unlike members of any other major religious group, most white evangelicals said immigrants represented a threat to America’s customs and values. Fifty-seven percent said that immigrants threatened American society, while 43 percent said immigrants strengthened American society.

Protestants of color expressed much greater support for immigrants. About 63 percent of Hispanic Protestants and 67 percent of black Protestants said that immigrants strengthened American society.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto, executive director of the progressive Christian group Evangelicals for Social Action, told HuffPost she believes the Bible consistently calls Christians to welcome strangers and extend hospitality to foreigners. She suspects some white evangelicals aren’t reaching the same conclusion because they aren’t aware of “how close their own immigration stories are.”

“With the exception of first nations people and enslaved African Americans, everyone else immigrated or sought asylum in this country,” Toyama-Szeto wrote to HuffPost. “[Many white evangelicals] are not aware of the circumstances of Grandpa Joe, and how their family stories might be very similar to the stories that are being played out in the news.

PRRI’s survey was conducted among a random sample of 2,509 adults in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., online and by telephone, between Sept. 17 and Oct. 1.

While statistics about white evangelical Protestants are easy to find, it’s harder to pull out data about evangelicals of color. PRRI and other research groups identify evangelical Christians by asking respondents if they describe themselves as “born-again” or “evangelical Christian.” This question helps researchers separate out white evangelical Protestants as a religious group. PRRI CEO Robert Jones told HuffPost that this reflects how white evangelicals and white mainline Protestants distinguish themselves on the ground ― using distinct denominational structures, for example.

But Jones said the general consensus in social science circles at the moment is against separating out black evangelicals of color, since black churches don’t have a similar divide between those who consider themselves evangelical and those who don’t. And for other racial and ethnic categories, the sample sizes obtained in public opinion surveys aren’t big enough to break out evangelicals of color with confidence.

PRRI’s 2017 American Values Atlas, an annual survey of approximately 50,000 people, indicated that 63 percent of black Protestants and 70 percent of Hispanic Protestants identify as evangelical ― suggesting there is significant overlap between black and Hispanic evangelicals of color and black and Hispanic Protestants of color.

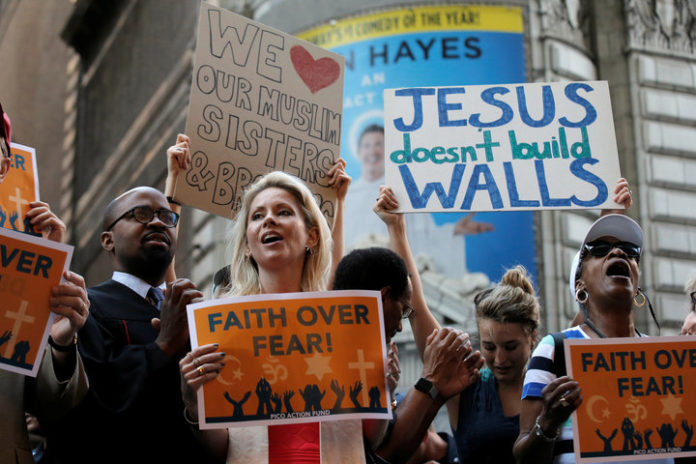

Brendan McDermid / Reuters

PRRI also found that many white evangelicals don’t have positive views about America’s growing racial and ethnic diversity. PRRI asked survey participants how they felt about the fact that the U.S. census projections show that by 2045, African-Americans, Latinos, Asians and mixed racial and ethnic groups will together comprise a majority of the U.S. population.

Again, white evangelicals were the only major religious group in which a majority expressed negative feelings about this demographic change, PRRI reports. Fifty-four percent of white evangelical Protestants said that America becoming a majority-nonwhite nation by 2045 will have a mostly negative effect on the country.

On the other hand, most black Protestants (80 percent) and Hispanic Protestants (79 percent) thought the country’s coming racial and ethnic realignment will be mostly positive.

Andrew Whitehead, a sociologist at Clemson University who studies religion, told HuffPost he thinks Christian nationalism, an ideology that fuses Christians’ love of God and country, influences how white evangelicals think about race, immigration and diversity.

“For white evangelicals, the idea of the United States as a Christian nation serves to solidify racial and ethnic boundaries around national identity, which then serves to bolster anti-black or anti-immigrant prejudice,” Clemson said.

Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Respondents’ racial identities also affected their opinions about how racism manifests itself in America. For example, white evangelicals and Protestants of color are deeply divided about the root causes of police violence against black Americans. The vast majority of white evangelicals (71 percent) believed that recent police shootings of African-American men are isolated incidents. Just 15 percent of black Protestants say the same ― most believe that these killings of black men are part of a broader pattern of how police treat African-Americans (84 percent).

In addition, some critics have suggested Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric has emboldened white supremacists. The criticism escalated after Trump declared himself a “nationalist” at a campaign rally last month, proudly embracing a word that has a long, troubling and overtly racist history.

Toyama-Szeto told HuffPost she “absolutely” believes there is a connection between the president’s rhetoric and the emboldening of white supremacist groups.

“We have always had racial violence―and we probably will in some forms. But what has changed is the way that the rhetoric from the top has made space for people to express what was socially not acceptable,” Toyama-Szeto said. “And that rhetoric has led to action―violence like we’ve seen in the past weeks.”

In the PRRI survey, conducted weeks before the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, researchers found that most black Protestants (75 percent) and Hispanic Protestants (63 percent) said they believed that Trump’s decisions and behavior had encouraged white supremacists.

On the other hand, white evangelicals were less likely to see a connection between Trump and white supremacists. Only 26 percent of white evangelicals said Trump’s decisions and behavior have encouraged white supremacists.

Toyama-Szeto said she believes that these gaps in opinion between white evangelicals and Protestants of color are partly due to the fact that these groups don’t often worship in the same spaces.

“When you don’t have access to other people’s experiences―especially across ethnic, economic, and geographic boundaries―it can be easy to default and care only about the issues that affect you, your family, and your friends,” she wrote.

Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

Gerardo Marti, a sociologist at Davidson College who studies race and religion, told HuffPost that Protestants of color have long understood that there is a cultural gap between their lives and the lives of their white co-religionists. But white Christians have a hard time believing that their own racial backgrounds deeply inform their attitudes.

“They do not understand it as ‘racism’ and refuse to acknowledge it as such because they do not believe they have hateful attitudes toward black people they know,” Marti said.

These divisions in opinion about immigration and racism are occurring at a time when American evangelicalism is actually becoming more diverse. As a whole, evangelical Christians are still predominantly white. But about 35 percent of evangelicals are not white, according to PRRI. They identify as black, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander, Native American, or part of some other racial or ethnic group. That percentage is only likely to increase, researchers say, not just because America is becoming more diverse but also because young white evangelicals are leaving the church.

In the long run, Marti said he thinks white evangelical churches will boast about their increasing racial and ethnic diversity. At the same time, he predicts leaders will try to obscure underlying conservative social and political attitudes about abortion, immigration, homosexuality and racial justice, focusing instead on the individual and his or her personal spiritual relationship to God.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI via Getty Images

As American Christianity gets more diverse, Marti thinks white evangelicals may increasingly perceive themselves as an oppressed minority.

“It may be strange to say, but once the white demographic moves under 50%, it will further energize their belief that they need to fight to protect their way of life, one they believe is called for and sanctioned by Jesus himself,” Marti wrote.

Toyama-Szeto believes the biggest challenge for white evangelicals in the future is whether they will be able to work with and accept the leadership of Christians of color.

“The white church can choose whether it wants to preserve its power but risk relevancy―as the issues they care about begin to drift from the mainstream conversation, as their numbers dwindle,” she said. “Or it can figure out how to build bridges and engage with a variety of communities, which will help them keep a finger on the pulse to know what people care about today.”